What Though the Odds

Meet Dawn Parkot.

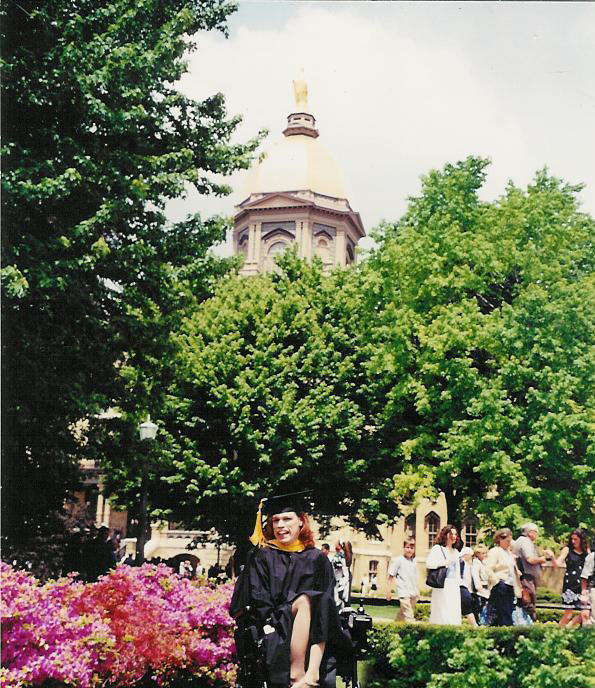

The 44-year old Morristown, New Jersey resident has been an alternate for the Para-Olympic equestrienne team, a double Domer (B.S. in mathematics, cum laude, 1995; M.S. in computer science and engineering, magna cum laude, 2000), and a state beauty pageant winner. A sought-after public speaker, Parkot serves as president and CEO of her own educational/inspirational organization while championing civil rights on local and national fronts. She’s also a beloved daughter, granddaughter, sister, and friend.

Why, you may ask yourself, would a person like her ever be the cause of a bar brawl, let alone multiple bar brawls?

Parkot has cerebral palsy. She can’t walk, has limited function of only one of her hands, a major speech impediment, and she’s legally blind.

“If I’m on a date, God help whoever assumes that I don’t have a fully working mind, because each of my boyfriends has always gotten in people’s faces to straighten them out on how smart I am,” Parkot relates good-humoredly.

“I am not limited!” She is emphatic. “I have to do some things differently than others, and it may take me longer, but so what? No big deal. When there’s a will, there’s a way.”

“I have to do some things differently than others, and it may take me longer, but so what? No big deal. When there’s a will, there’s a way.”

Initially, the will belonged to her parents, who refused to believe doctors’ diagnoses that their daughter – born with brain damage – would remain a mindless vegetable and never make it to her fifth birthday. While Parkot’s father was deployed to Korea, her scientist mother got busy researching cerebral palsy at the library.

An institute in Philadelphia was pioneering a treatment program in which specific exercises were repeatedly performed on people with brain injuries until the brain learned for itself how to control movement and function normally. Parkot’s mother learned the techniques and worked six and seven hours a day, every day, for years, with her daughter’s body to stimulate her muscles and create cerebral muscle memory.

“We were driving cross-country more than once and my crazy mother would pull over to truck stops and ask truck drivers to help with my therapy, because one of the exercises required three people. You can imagine the looks they gave her, but no one ever refused to help her with me.

“I despised some of those exercises, and that therapy was the source of many battles with my mother, especially when I was an unruly teenager,” Parkot admits. “But my mother’s tough love and refusal to give up on me helped me enormously.”

Therapy and tenacity allowed Parkot to take her first independent steps at age eight. However, on the brink of finally being able to walk, she came down with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. No longer able to handle hours of therapy every day, she had to accept the fact that she would always need a wheelchair.

Just like any child, though, Parkot had dreams and goals for her life. In fifth grade, she informed the teacher that “I was going to attend a top university, have a successful career, marry Mr. Right, and be a mother someday. Additionally, I wanted to be an Olympic champion and win a beauty pageant complete with a tiara!”

The school immediately called Parkot’s parents in for a conference and insisted that they quell all such “fantasies.” Her parents responded by pulling their daughter out of the school, threatening the school district with a law suit and mainstreaming Parkot in the local public school system.

Even with such devotion and relentless advocacy, her parents could not protect her from every bump in the road. When she was 16, Parkot’s power-wheelchair hydroplaned off a cliff while she was volunteering at a camp for young Girl Scouts. The accident caused spinal cord trauma and additional brain injuries, leaving Parkot without control of her right side, without feeling in her upper body or arms, and in constant pain. Legal blindness resulted, as did temporary regression of mental capacity.

The doctors and therapists at the specialized hospital where she received treatment believed she did not need more than 40 minutes of therapy a day because they saw her case as hopeless.

“I knew my mind would be the ticket to my success in the real world,” Parkot recounts, and admits that she battled a grave depression during that time.

Later that year, doctors discovered a tumor on her right hip. Removing it required surgical detachment of her leg and insertion of a large screw to put it back together. Again, her therapy had to be decreased in favor of convalescence.

“I was extremely angry at God, but deep in my heart I knew he would show me the road back. Psalm 107:28 reminds us, Then they cried to the LORD in their trouble, and he brought them out of their distress.”

When there’s a will, there’s a way. Her grandmother also had that will, and was a haven of hope extending comfort and assurance far beyond the years of her life.

“She knew what I thought, how I felt, and what I wanted and I never had to speak,” shares Parkot fondly. “To my mother’s chagrin, she introduced me at a young age to the finest things in life: shellfish, lobster, crab, and shrimp, and Saks Fifth Avenue, where she bought me a baby-blue linen Easter dress with matching coat, that were both dry-clean only, when I was two years old. My mother could not understand why anyone would get an ensemble like that for a messy toddler, but she had to give in to Grandma Kelly’s will.”

"I’m living proof that persons with multiple extreme disabilities can have full, happy, rewarding, and successful lives.”

In her day, Grandma had been a New York City ballet dancer and was intentional about introducing Parkot to classical music and balletic movements, along with Grimm’s fairy tales and other literature. “Her reading was better than a movie,” Parkot recalls.

Her grandmother also introduced Parkot to her future alma mater.

“My grandfather attended Notre Dame, and Grandma used to tell me stories about visiting him there. She made it seem like a magical place, and I thought if I went there then all my desires would come to life.”

Though heavily recruited by Yale and Seton Hall, she could not deny the allure of Notre Dame. On the night she graduated from high school, Parkot’s parents presented her with her grandfather’s 1947 class ring, a gift she was unaware her dying grandmother had reserved for her many years prior.

Parkot says that when she arrived on campus the University had limited accessibility and inclusion protocols because she was the first student with such serious disabilities. Her mother spent a few weeks training volunteers to assist Parkot with day-to-day activities, and then “just like any other college student, I was on my own, which I dearly loved. I was free to party as much as I wanted!”

Parkot excelled academically and socially and flourished spiritually at Notre Dame.

“The reason I have been successful is that God put special individuals in my life like my two best friends: Kevin Richter (’97) and Dr. Joe Turbyville (’93). Because of them, I am able to overcome whatever comes my way. They have stood by me for years, through school and health issues, breakups, family struggles… I will always be grateful for their friendship,” Parkot shares.

Her other major inspiration? Parkot has been a lifelong Mets fan.

“In the summers, I eat, sleep, and breathe New York Mets. During the ‘80s when I had illnesses, brain injuries, and long hospital stays, I watched every game on TV. The Mets got me through and took my mind off whatever I was going through."

With Gary Carter, the catcher from the New York Mets, the 1986 World Series Champions

With Gary Carter, the catcher from the New York Mets, the 1986 World Series Champions

And that’s the thing: Parkot is extraordinary in her ordinariness. She stands out because of her ability to fit in.

“I’m like most Domers: with my gifts from God, I want to make a difference in the world,” she explains. “As a Catholic, it’s my job to speak and lead in a constructive manner because I’m a very well educated woman with public speaking skills. I’m living proof that persons with multiple extreme disabilities can have full, happy, rewarding, and successful lives.”

How does someone with a major speech impediment end up with a career as a public speaker?

“I have a DynaVox V-Max, the same speaking device as Stephen Hawking (the noted physicist who has ALS). I first write my presentation on my big computer at home, then transfer it into my speaking device. The words have to be spelled phonetically so the device will speak the word correctly. I use my left hand to hit one button, which speaks one paragraph at a time during my speaking engagements. I can give brief answers to questions, if people ask, but often I have people email me their questions so I can take the time to answer more fully.

“Yes, it takes me a lot of time to prepare a presentation, but so what? The world needs me to speak and fight for the lives and rights of the disabled,” she states resolutely.

The Climb Organization, which Parkot founded in 2009, is the vehicle for her platform. Its mission is twofold: motivating all people to get passionate about their lives and go after their dreams, and educating the world on end of life and disability issues.

“The disabled community just wants to be included. Injustice and exclusion occur because of the way the world thinks about us. We are not seen as human beings, made in the image and likeness of God, but as inconvenient things for people to cope with.

“For years, people have been taught that dealing with a disabled person requires special skills that [are tantamount to] a medical degree. Perhaps the greatest sources of segregation are the medical and social services establishments. But a new, fresh wind is blowing through these bastions of second-class citizenship. On a grassroots level, a lot of the disabled community and I are saying ‘Enough!’ Separate is frequently not necessary and certainly never equal. Just let us get on in our own way, among you.”

Parkot outlines four ways anyone can join her in making the world a more inclusive, loving place.

- Vote in every election, exercising your responsibility to participate in decisions that affect human quality of life.

- Pray for legislators, judges, and other elected officials who make decisions affecting the unborn, the sick, and those who are disabled.

- Talk with your friends and family about the gift of life and teach your children to respect everyone’s life.

- Ask questions! It’s ok if your children (or you!) stare and want to know what happened to someone who’s in a wheelchair or who looks different from able-bodied people. Those questions are natural, and shushing them or moving quickly past does nothing except create fear.

In his letter to the Galatians, the apostle Paul wrote that “in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Dawn Parkot lives her life in witness to this equality under Christ. Far from deriving her worth from beating the odds, or as a paradigm of persistence, or being reduced to a political icon or moral object lesson, her value is in being who she is – a person, seeking God’s will as she’s making her way in the world. Just like you and me.