A POW Returns to Japan

Last month, William Howard Chittenden ’49 left his home in Wheaton, Illinois and traveled halfway around the world to Japan. For a week and a half, he visited historic sites and sampled the authentic local cuisine.

But Chittenden was not your average tourist. The 95-year-old was an invited guest of the Japanese government. And it was his first time back in the country since he spent 1,364 grueling days as a prisoner of war seven decades ago.

Chittenden joined eight other former American POWs on the trip. They had been invited by the Japanese Foreign Ministry as part of a reconciliation program that launched five years ago. The group met with Japanese government officials, attended a reception at American Ambassador Caroline Kennedy's residence, and visited some of the places they had been held captive.

“By the time it was over, I was worn out,” Chittenden says. “It was very exhausting but very entertaining and very interesting.”

The whirlwind tour served as a redemptive return to a place that had caused Chittenden so much suffering and left him with a lifetime of difficult memories.

A Path to College

Chittenden grew up in the Midwest during the Great Depression. Like many, his family did not have much money, so college was not an option after high school graduation. He found a job as a drugstore clerk in Villa Park, Illinois but grew frustrated as he watched some of his friends from more well off families progress through college.

“I decided I’d join the Marine Corps, see the world, and save some money,” Chittenden remembers. “And then go to college later in life.”

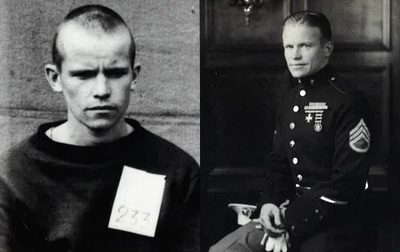

He entered the Marines in Chicago in late October 1939. A month earlier, Germany had invaded Poland, plunging Europe into another world war.

Chittenden attended boot camp in San Diego. He then was sent to Bremerton, Washington, where he worked guard duty at Puget Sound Navy Yard. After just a month, Chittenden answered a call seeking volunteers for assignments in Asia. He shipped out of Bremerton in March 1940 and arrived in Peking, China on May 5.

Chittenden was one of 450 Marines assigned to guard the American embassy in Peking. “It was some of the best duty in the Marine Corps,” he says. Chittenden loved the work, but by December of 1941, his stint in China was coming to an end. He had been ordered to return to the United States to attend officer training school.

Three days before his scheduled departure, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. The Japanese had already invaded in China in 1937. Now at war with the United States, Japanese forces held the American troops in Peking captive.

Just days away from his scheduled return to the United States, Chittenden was now a prisoner of war.

Life as a POW

“At the time, we thought the war would be over in six months,” Chittenden remembers. “That was our attitude about it.”

That turned out to be wishful thinking. He spent the first year and a half in two separate prison camps outside Shanghai. The camps were run by the Chinese, and Chittenden remembers being treated relatively well. In August of 1943, he was transferred to Japan.

“It was a different thing entirely.” he remembers. He says the Japanese tended to view prisoners of war with contempt. “To them surrender was a humiliating thing. That was the way they looked at us.”

His new prison camp in Kawasaki, Japan was situated near a steel mill. Each day, Chittenden and his fellow POWs were marched to the mill, where they were forced to work long hours in dangerous conditions. In June 1945, after the U.S. bombings of Kawasaki, Chittenden was moved to a camp in Niigata, where he was made to load and unload cargo for a transportation company. It added up to two years of intense slave labor.

Meanwhile, the prisoners were fed barely enough to survive, and the food they did receive lacked essential nutrients. While Chittenden was never physically tortured, other prisoners were. The most painful element may have been the psychological effects of captivity. “You knew it was going to end one way or another. Either you’re going to die there, or you’re going to get home. You never knew which your fate would be.”

"Either you’re going to die there, or you’re going to get home. You never knew which your fate would be.”

Chittenden learned of his fate on August 15, 1945, a day he calls one of the happiest of his life. The Japanese surrendered, and within weeks he was on a plane back to the United States. He was brought to a Navy hospital in Oakland, California. Chittenden’s normal weight was 150 pounds, but he was down to 100 when he arrived at the hospital. “It was a tremendous relief to finally get back to where you weren’t constantly hungry.”

A Dream Realized

Once back to full health and honorably discharged from the Army, Chittenden set out to fulfill his original goal of attending college. With the help of the GI Bill, he knew which school he wanted to attend. “The sisters in grade school, they always preached Notre Dame,” Chittenden says. “And so I was brainwashed by the sisters.”

Chittenden enrolled in March 1946 as a 26-year-old freshman. He majored in marketing with a minor in philosophy and graduated in just three years. Most importanty, Chittenden met Patricia O’Connor, a student at Saint Mary’s. The couple got married in 1949 and went on to have three children together. After graduation, Chittenden accepted a job at Sears, Roebuck & Company in Chicago. He retired from the company in 1980 as the quality assurance manager in the men’s sportswear department

Through it all, Chittenden stayed connected to his wartime experiences. He and many of his fellow North China Marines would meet periodically for reunions. And after he left Sears, Chittenden felt compelled to share his memories. “No one had ever told anything about us,” he says. “I felt that somebody ought to write something and put our story in history.” His book, a detailed and fascinating account of his service career and the experience of being a prisoner of war, was published in 1995.

Back in Japan

The trip to Japan in October was filled with poignant moments. On the first day, the group visited Yokohama War Cemetery, where there is a memorial to the prisoners of war who died. The nine POWs were invited to enter the crypt, which contained a mass urn holding the ashes of over 300 falled troops. Confined to a wheelchair, Chittenden wasn’t able to enter, but he sat outside and saluted the deceased.

They also made a stop in Kawasaki at the steel mill where Chittenden worked for two years. Inside the mill, he came across a sketch of the prison camp. Chittenden noticed something amiss. In the sketch, the camp was set up for 160 prisoners, but there were actually 250 men there at the time. Chittenden brought a copy of the sketch back to Wheaton, where he plans to correct it and mail it back.

The experience offered Chittenden some closure on the most difficult chapter of his life. Still, some things continue to nag at him. Perhaps the biggest is the regret he carries that he never had the opportunity to defend his country in battle.

“When I think of what fellows did that could contribute to the war effort, we were never able to do that. And that has always bothered me,” he explains. “I say this for myself and I think for every other man that was with me. We would all have rather taken our chances of coming through the war in combat than as prisoners of the Japanese.”